What do we mean by cultivation when it comes to the northern parts of Norrland and its prehistory?

In the research program Cultural Heritage, Landscape and Identity Processes in Northern Fennoscandia 500-1500 AD, we try to break up old patterns of thought, find new pieces of the puzzle and build a new history. The landscapes of cultivation, reindeer husbandry, hunting, fishing and trade are in focus in a collaboration between archaeologists, ecologists, forest historians, historians, soil chemists and place name researchers.

Now, in the second half of the program, we can present results that turn old truths upside down, not least when it comes to the history of early cultivation.

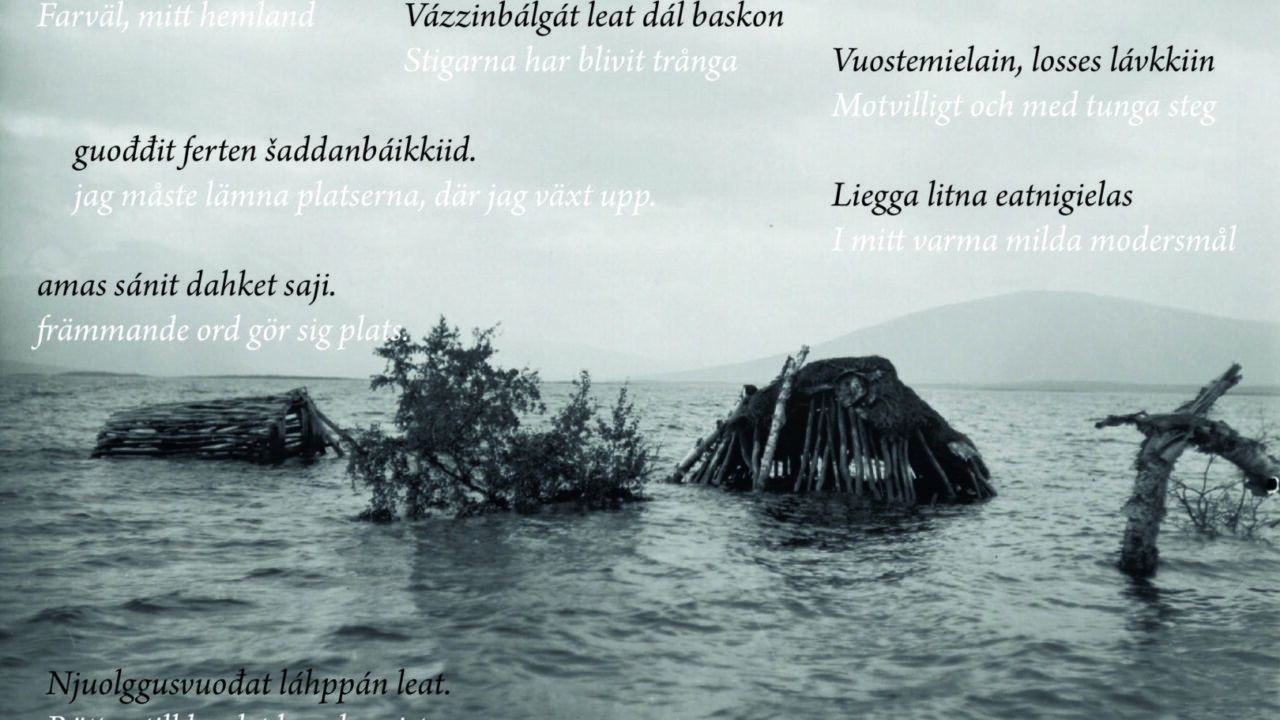

Traces in the form of pollen from cereals are found from the 8th century AD onwards at several locations west of the Lapland border in landscapes considered to be Sami. These are new findings published in the scientific journal The Holocene by researchers at the Institute for Arctic Landscape Research at the Silvermuseet in Arjeplog, and described in a forthcoming issue of the magazine Popular Archaeology.

The observations form a pattern in both time and space that questions our previous picture of how humans have used the landscape in Norrbotten's hinterland is really true.

"Our interpretation is that the traces indicate small-scale, temporary cultivation that complemented hunting, fishing, gathering and animal husbandry," says Greger Hörnberg, a researcher at the Institute. The traces have also been found in previous studies, but they have not been noticed because they do not fit the common perception of the history of farming in the north.

"Grain farming has been strongly linked to a coastal farming community and has not been associated with the Sami way of life until the 19th century when many Sami became small farmers," says Ingela Bergman, archaeologist at the Silvermuseet.

But we also know that the Sámi used a range of plants in their diet, and that they sowed juobmo (mountain sorrel) and turnips on old pastures, and from there it's not a long step to incorporating grains.

"The results are exciting as they show a more complex landscape utilization early in the hinterland and put old perceptions in a new light," concludes Ingela Bergman.